By Jim Goyjer

(15 min read)

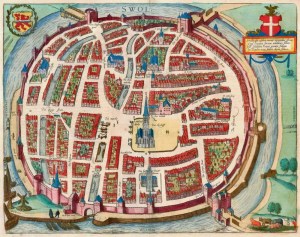

Zwolle is a small city located in Northeastern Netherlands, and it is the capital of the province of Overijssel. Zwolle is a student town with three universities. It’s a hip city that radiates a historic past and a vibrant present. The city center has numerous historical landmarks interspersed with boutiques, cafés, museums, hotels, restaurants, pristine parks, a few coffee shops, and an artificial beach in the summer. The old town is surrounded by the Stadsgracht (City Canal) lined with sections of the Medieval city wall. The populace is known as “Blauwvingers” (Bluefingers). I’ll explain later.

The area has been inhabited since the Bronze Age, around 4,000 years ago, by hearty fur-draped people. Zwolle was founded around 760 AD by merchants and troops of an ancient German tribe called Frisians. They named the region around the settlement Frisia. Made sense. Today it’s called the Province of Friesland. The name Zwolle originated from the word “Suolle,” which means “hill” in either old German or old English, because the city began on a hill surrounded by three rivers, IJssel, Vecht, and Zwarte Water. The mound was the only place that remained dry during frequently occurring river floods. Over three thousand years, “Suolle” morphed into “Swell” then into “Zwolle.” No matter what it’s called, it’s a swell city.

The bishop of Utrecht granted Zwolle city rights in 1230, and it became a member of the Hanseatic League in 1294. The city was the largest Hanseatic League city on the Ijssel River. The League was a trading network that began with a few North German towns in the late 12th century. It expanded between the 13th and 15th centuries and eventually included nearly 200 coastal and river settlements, with trading posts from Russia to Portugal and from Finland to the Mediterranean. It was an early version of the European Union.

Because the town was located on the junction of three rivers, it was the perfect place for trade between Scandinavia and the Rhineland via the North Sea and the old Dutch Zuiderzee (South Sea), which is now a lake thanks to a long dike built around 1930 separating the two seas. Much of the former Zuiderzee is now reclaimed land. If you want to get to the North Sea today, you must jump over a big dike.

Zwolle became very prosperous in the 14th century. Too wealthy for some. In 1324, a group of disgruntled noblemen, led by ignoble Roderik van Voorst, were jealous of the city’s success and set fire to Zwolle. Roderik and his ilk were losing their stature as lords of Overijssel province. Most of the structures were made of wood with thatched roofs, so burning them to the ground was easy. Only nine stone buildings survived the fire. After the flames died down, brick-built buildings and houses were preferred over wood, just in case miscreants came back.

And they came back. In 1361, the city was again besieged by fire. This time by Zweder van Voorst, Roderik’s son, who came into direct conflict with Zwolle. The city had planned a canal connecting it to the Ijssel River that would cross Zweder’s land. Suspecting that he would not receive a share in the financial income from the trade traffic, Zweder set fire to Zwolle.

The citizens didn’t take kindly to the second onslaught by the Voorsts. They formed an army and attacked Zweder’s castle and its inhabitants. Eventually, they had to surrender. They had no choice. The attackers threw carcasses and other waste into the castle’s moat and over the walls. This created a horrendous stench and poisoned the drinking water. Zweder fled and died in exile, in 1363 from heartache. His ancestral Voorst Castle was destroyed, and the stones from the ruins were put to good use. They were repurposed to pave a road from Zwolle to the town of Kampen, 16 kilometers (10 miles) away. From destruction to infrastructure.

Zwolle’s famed rector, Johan Cele, is considered the historical founder of the Dutch public education system. From 1375 to 1415, he introduced the grammar school, an educational system that was adopted throughout Europe and that contributed greatly to the reform of the Catholic church and society. He educated his students in the ideals of Modern Devotion. Modern Devotion was a movement that rose out of widespread dissatisfaction with the Church’s bureaucracy and the holy bubble lifestyles of the clergy.

The movement called for the renewal of moral practices such as humility, obedience, simplicity of life, and community mingling. It advocated for the humanistic principles of universal human dignity that included individual freedom and happiness. These edicts were precursors to the later Age of Enlightenment or the Age of Reason in the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe, when deism emerged. Deists believed in God based on reason rather than the dogmatic teaching of any specific religion. Several of America’s founding fathers were deists, such as Thomas Jefferson.

Zwolle has several distinctive landmarks. In the 15th century, the town was surrounded by a fortified wall with 23 towers. Built in 1409, the Gothic Sassenpoort city gate is the only tower left that was attached to the old city wall. This gate is listed as one of the Top 100 Dutch Heritage Sites. The Peperbustoren (Pepper Shaker Tower) is a 75-meter-high tower of the Basilica of Our Lady. The unique tower looks like a pepper mill and can be climbed to the top. The tower is so famous that it has a cheese named for it, peperbuskaas (spicy pepper shaker cheese). It’s an acquired taste.

Repurposing churches from houses of worship into more practical uses is widespread in the Netherlands. The old Broerenkerk (Brothers Church), founded in 1465, was repurposed in 1988 from a protestant church to a magnificent cultural center replete with a gift shop, bookstore, and café.

On Bethlehemkerkplein (Bethlehem Church Square) is another repurposed church. Bethlehemkerk (Bethlehem Church), built around 1309, was a chapel of the Bethlehem Monastery and one of the oldest buildings in Zwolle. The chapel was spared during the city fire in 1324. The chapel was expanded in the middle of the 14th century to be baptized as a church. The church is now an all-you-can-eat Japanese sushi restaurant.

A former 19th-century courthouse until 2005, the Museum de Fundatie houses a collection of art works ranging from the end of the Middle Ages to the present day. The museum was enlarged in 2012-2013 with the addition of a new and unusual egg-shaped bubble on top of the building’s roof for additional exhibition space in its yolk. The collection contains over 7,000 paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, and other objects. Among these works are paintings by Marc Chagall, Piet Mondrian, Vincent van Gogh, and other renowned painters.

St. Michael’s Church was first mentioned in 765 AD in some Roman archival document or blog. A Romanesque church was erected around 1040, which stagnated over time. The current three-aisled Gothic St. Michael’s Church was built on the same spot between 1406 and 1466. In 1578, during the Reformation, the Catholic church was converted to a Protestant church. It dominates the town’s Grote Markt (main square). Today, it’s used for art and cultural exhibitions. Sorry, no bingo.

Now to the “Blauwvingers” (Bluefingers). In 1682, St. Michael’s church tower collapsed due to a heavy storm causing lightning bolts to strike the tower. The town was going through some tough times and had no money to make the repairs. Strapped for cash, the city elders decided that since there was no church tower left to hang the bells, they should sell them to the town next door, Kampen. To make some money on the deal, Zwolle’s dealmakers negotiated a hefty price for the weighty church bells. Kampen accepted the offer, and when the bells arrived, they were damaged and did not ring-a-ding-ding. In revenge, Kampen paid in small denominations of copper coins. Zwolle distrusted Kampen and wanted to be sure they truly paid the full price. After rigorously counting this vast number of coins, their fingers turned blue from the copper. Hence, the residents were thereafter named “Bluefingers.”

Zwolle’s golden age was in the first half of the 15th century, because of lucrative trading links and local agriculture. The town remained relatively quiet and prosperous until 1555, when Spain occupied most of the Netherlands. The Dutch War of Independence, between 1566 and 1648, from Spain also took a toll on the economy. Even the occupying forces of France under Napoleon in the 18th century didn’t help boost its fortunes. The city just lingered along.

Economic growth returned in the 19th century with the introduction of the railroad in 1864, linking it to the rest of the Netherlands. Zwolle expanded its industrial base, developed its educational institutions, and improved infrastructure, which transformed it into a modern city.

When the Germans invaded and occupied the Netherlands between 1940 and 1945, the Nazis valued Zwolle during World War II. It had become a major railway transportation hub. Because of its strategic importance, the Dutch resistance carried out numerous acts of sabotage on the railroads near the city, especially in the days leading up to its liberation. The Germans imprisoned, tortured and executed many resisters, as well as Jews, all of whom were sent to concentration camps.

A remarkable heroic story of cinematic proportions happened during the liberation when a French-Canadian soldier, Private Léo Major (1921–2008), single-handedly liberated the city from the Germans. On April 13, 1945, the Régiment de la Chaudière, a primary reserve infantry regiment of the Canadian Army, reached Zwolle. Because it was reported to be a German stronghold and before firing artillery on the city, the commanding officer asked two volunteers to go on a reconnaissance mission to scout the German force. Private Major and his friend Corporal Willie Arseneault stepped forward. To keep the historic city from being destroyed, the duo decided to try and capture Zwolle by themselves.

Around midnight, Arseneault was killed by a German soldier. Infuriated, Major decided to continue the mission alone. He entered Zwolle near Sassenpoort, and the rest is a Hollywood movie, except that his exploits were real. He stormed in and out of the city almost a dozen times during the night with his submachine gun blasting away, crisscrossing streets, running around buildings and private homes by tricking the local German garrison into believing that there was a much larger Canadian force attacking the town.

Overnight Major killed a few SS officers, captured and delivered several groups of German POWs, and burned down the Gestapo headquarters. At 4:30 in the morning, the rest of the Germans had left. With the help of some courageous citizens, Private Major preserved the city for posterity. Walking through the city, one can only imagine what it would have been like without Private Major’s heroic feat. Major was made an honorary citizen of Zwolle in 2005, and a street was named for him.

There are numerous restaurants and historic hotels in Zwolle. But the 5-star De Librije Hotel with its 3-Michelin-star De Librije Restaurant is historically unique. The building was constructed in 1739 as a prison. Men, women, and children existed together in a confined space. When the number of prisoners began to increase and cells were introduced to separate the inmates, it became difficult to breathe fresh air within its shrinking area.

The prison became known as the “Spinhuis” (Spinhouse) when, in January 1742, a few spinning wheels were delivered to circulate air. Healthy inmates were able to earn a living in prison by spinning the wheels, just like hamsters. Eventually the building was no longer suitable as a prison. It was closed in 2006.

Spinhuis spun into a luxury hotel/restaurant after the former prison was bought in 2007. Today, men, women, and children who are related can lodge together in their own rooms with air conditioning in a building that was once a penitentiary. From confinement to refinement. That’s progress.

Zwolle is worth a day trip. It has Medieval facades, a star-shaped city moat, lined with stately merchants’ homes, aged trees, fountains, sculptures, and sections of the old city wall and fortifications (the ramparts were destroyed in 1674 during the Anglo-Dutch Wars). You can even splurge by dining and sleeping in a former prison.

(Banner Photo Courtesy of Zwolle Marketing – Copyright (©) Zwolle in Beeld 2024)

hi Jim & Nanci

What a great review about Zwolle I didn’t know that !

Thanks. Gemma