By Jim Goyjer (15 min read)

The historic small city of Schiedam in the Dutch province of South Holland is known for its canals, shipbuilding, herring fishing, having the tallest windmills in the world, but most importantly, for its jenever, the predecessor of gin. It has historically earned the title of the “Jenever Capital of the World.” On the sober side, the town is also known for Saint Lidwina, one of the country’s most famous saints and the only female saint in the Netherlands. On the sinner side, it’s where the last Dutchman was executed for homosexuality.

Schiedam was founded around the year 1230 on the banks of the Schie. The Schie was a large stream that flowed into the Maas, one of the many tributaries of the Rhine leading to the North Sea. Although the Schie was no more than a stream, it was dammed by a local lord to protect the existing reclaimed land, known as a polder, against the seawater from the North Sea. The dam morphed the stream into a small river, creating a commercial waterway.

In 1247, aristocrat Lady Adelaide of Holland married a wealthy Count who endowed her with the land east of the dam, together with the adjacent polder. The dam’s locale attracted trade to and from towns upstream, such as Delft, Leiden, and Haarlem. Those goods had to be transshipped from river barges to seagoing vessels. Around the dam, a small town emerged that quickly developed into a major distribution center with warehouses and service facilities. Merchants, skippers, and artisans arrived, and the dam town on the Schie became Schiedam.

In the same year, Adelaide also wanted to build a church to show-off Schiedam’s prestige. In December, she obtained permission from the Bishop of Utrecht to build Sint Janskerk (St. John’s Church). A Christmas present. The original 1262 church was replaced by a more impressive building in 1335, as Schiedam gained importance. It took 90 years to complete, including holidays, vacations, and family leave. Afterwards, the church was altered and restored many times to what it looks today.

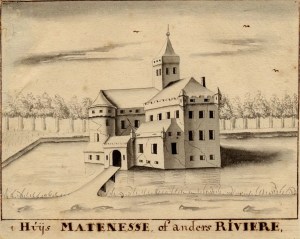

Schiedam received city rights from Lady Adelaide in 1275. That ability was given to her by her brother William II, the reigning Count of Holland and King of the Holy Roman Empire, that included most of Western Europe. The Lady had noble connections. Because of her stature, she ordered the building of a castle near the Schie and Maas rivers in 1262, and called it “Huis te Riviere” (house on the river). Catchy name.

This historic story sounds fishy, but it’s true. Noble Dirk of Mathenesse acquired the Riviere Castle in 1339. As the new lord of the realm, he named it after himself, Mathenesse Castle. Then, off-and-on bloody wars and battles broke out between Delft and Schiedam from 1350 to 1490. Called the Fishhook and Codfish Civil Wars, or the Hook and Cod Wars, it was an economic and political struggle pitting the liberal middle class in the cities against the conservative nobility. Delft’s working class were the Cods, and the ruling class of Schiedam were the Hooks. The clashes were ultimately about who would become the next Count of the County of Holland: a liberal or a conservative. The Hooks were defeated in 1490, after one of the many exhausting, nonsensical battles. The victorious Cods were supported by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. It was a good outcome for the liberals.

Dirk died in 1345, in his twenties. The castle was granted to Dirk’s brother, Daniel, a Hook. The Cods destroyed his castle in 1351. Daniel switched sides and became a Cod. When Daniel died, the castle was bequeathed to his Codly sister. The place was remodeled, and when the castle was almost finished, it was destroyed by the Hooks in 1426. Dammed if you do, dammed if you don’t.

Meanwhile, during the angling matches, Schiedam’s elite became increasingly rich by levying canal tolls. It was a monopoly, and the Hooks were price gouging. Delft’s Cods decided to dig their own canal, connecting the city directly to the Maas river, bypassing Schiedam, and those high fees. The canal took away a lot of Schiedam’s transport business. The herring industry remained Schiedam’s only major economic resource until a saint came marching in.

Pilgrims came flocking to Schiedam for either Lidwina or booze or both. The city had become famous for the production of jenever, the predecessor of gin. Jenever is the Dutch word for juniper. Juniper berries had been around as far back as around 1500 BCE in ancient Egypt, when juniper berries were used to cure tapeworms. In the Middle Ages, juniper juice was used for various medical purposes, such as an antidote against the plague that plagued Europe frequently.

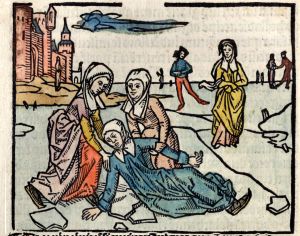

As the story goes, Liduina was born in Schiedam on Palm Sunday in 1380 in a family with eight brothers. At the age of 12, her father wanted her to marry someone in the neighborhood. She and her mom thought it was a better idea to marry the son of God. Liduina prayed to become unattractive to suitors. At age 15, she went ice skating with a few friends on the Maas River. She fell and broke a rib. Left untreated, she contracted gangrene and became paralyzed. Sick of being bedridden, she gave up her Catholic religion. When her suffering caused her to become suicidal, a spiritual advisor convinced her to return to Jesus.

After re-joining Jesus, Liduina experienced visions, raptures, and out-of-body experiences, such as traveling to Rome and Jerusalem on Virgin Airlines. Lying on her sickbed, she comforted the poor and the needy by telling them not to ice skate. Donations from thankful visitors she gave to feed the poor. Liduina died in 1433 and was buried in Schiedam’s Basilica of Liduina, which became a place of pilgrimage. Four and a half centuries later, the Pope granted her sainthood. She was bestowed the patron saint of Schiedam and of ice skaters, of course.

The world’s first known commercial liquor distillery started operations in 1575. Although Schiedam was occupied, off and on, by Spanish and French troops in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, all the occupiers supported the town’s many distilleries, especially those producing jenever. It was called “Juniper water” and sold as medicine or cough syrup. Coughing became a prominent malady among the troops.

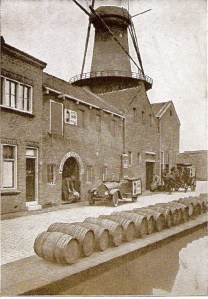

The 18th century was Schiedam’s Golden Age of jenever. The business flourished, helped by restrictions on the import of alcohol from France – a trade war – and from the decline in the herring fishing industry. Skippers looked for new revenue streams and preferred the smell of jenever over fish. More than one million bottles of jenever were produced every year around 1880 by 364 distilleries. Almost 95% of Schiedam’s jenever was exported throughout the world. Due to massive production, the town got its nickname “Black Nazareth.” The nickname came from the soot produced by the jenever and other distilleries that turned the city’s scape black. Why “Nazareth?” Only Jesus knows.

More than 30 tall windmills were built to catch the wind above the tall warehouses in order to grind the grain used to produce malt wine, an important ingredient in jenever. Malt wine, more commonly called mulled wine, was made by boiling red wine with orange slices, brandy, honey, cinnamon, cloves, and other spices until the flavors have merged into a smoothie. Malt wine dates back to ancient Roman times, when it was drunk to keep warm during winter.

Around the 1890s, many of the distilleries consolidated, and in order to boost profits, the larger distilleries started producing a cheaper form of jenever called “jonge” (young) jenever made from sugar beets or cane and a lower degree of malt wine. Today, that’s called “skimpflation,” which involves reducing quality or using cheaper ingredients to boost sales among the working class. In other words, greed. Sound familiar? Jonge jenever was easier and cheaper to make. In the 20th century, the antiquated, more expensive to produce, old jenever industry declined sharply.

There are seven of the tallest windmills in the world within Schiedam. Six of the original, built in the 18th and 19th centuries, are still standing. They are all within easy walking distance. The Noletmolen (Nolet Windmill) is the seventh and newest windmill in Schiedam. Built in 2005, at 42.5 meters (140 feet) high, it is the highest mill in the world. This one doesn’t grind grain; it generates electricity for the Nolet jenever distillery that dates back to 1691. It has been continuously owned by the Nolet family since its foundation. It’s one of the oldest family businesses in the Netherlands, lasting eleven generations. Jenever flows through their veins.

On a somber note, one person needs to be recognized for his sin and his impact on equality. On March 9, 1803, Jillis Bruggeman was the last person in the Netherlands executed because of his sexual orientation. He was hanged on the Grote Markt in Schiedam at the age of 53. He was a traveling salesman and was married twice. His first wife died, and his second wife divorced him. He had children with both wives, and according to research, he took good care of his families.

But Bruggeman was bisexual. He was being blackmailed for many years by one of his male partners, before a different confidante betrayed him. When rumors flared about indiscretions, he fled Schiedam, but kept in touch with his wife. Eventually, she wanted a divorce. Bruggeman went to Schiedam to defend himself in the divorce proceeding. When he arrived, he was arrested. The official charge was “vuyle ebuys” or “filthy desires.” During his undisclosed interrogation, Bruggeman pled guilty to ‘the crime of sodomy’ and was executed. Same-sex sexual activity was legalized in 1811 after France invaded the country and installed the Napoleonic Code, erasing any remaining sodomy laws. The Code stressed individual freedom, although mostly for men.

Now, Jillis Bruggeman is a symbol for the oppression of LGBTI people, and a foundation under his name is committed to their rights. There’s an annual Jillis Bruggeman Medal awarded to someone who has made a significant contribution to defending LGBTQ people. The award is presented by the Municipality of Schiedam together with the Jillis Bruggeman Foundation. In 2015, a Jillis Bruggeman memorial was placed on the Grote Markt in front of the old town hall, where he was hanged.

Meanwhile, at the end of the 19th and throughout the first half of the 20th century, the shipbuilding industry boomed in Schiedam, and some 7500 people were permanently employed during its heyday. Shipbuilding started to sink in the latter half of the 20th century. Through mergers and increased government support, the large yards remained sustainable until the 1980s. But in the end, the industry joined Davy Jones’ locker.

Schiedam resurfaced and is worth a day trip. Today, it’s a picturesque small city featuring canals, drawbridges, historic waterways, locks, and historic buildings, such as St. John’s Church, the town hall, and the ruins of Mathenesse Castle, which was destroyed in 1575 by the townspeople of Schiedam to prevent it from being used by invading Spanish troops. The Stedelijk Museum is a notable museum for modern and contemporary Dutch visual art. The National Jenever Museum operates in a former distillery and is worth a shot or a double shot. One can also join a workshop at the Distillers Academy situated in the city’s Dutch Distillers District. A more tranquil experience is an open boat cruise through the historic center that celebrated its 750th Birthday in 2025. Happy Birthday or Gefeliciteerd, Schiedam.

neat history of the city of Schiedham (hope i got it right!)

Thanks for reading the article and for joining my blog. I want to wish you a terrific New Year.

I learned a lot from your history lesson, Jim

and I like your humor.

Vriendelijk bedankt.