By Jim Goyjer

The Jordaan neighborhood of Amsterdam is one of the most iconic and beloved neighborhoods in the city. Not far from Central Station, the Jordaan is Amsterdam’s most emblematic district with its narrow streets, flower-lined canals, numerous bridges, specialty shops and boutiques, historic cafés, diverse restaurants, artists’ studios and galleries. More than any other part of Amsterdam, the Jordaan exemplifies a serene, picturesque atmosphere represented in postcards. It was not always this way.

In the 1600s, migrants started flocking to the wealthy city of Amsterdam, capital of the Golden Age, for jobs and a better life. These groups included German Lutherans, French Protestant Huguenots, Portuguese/Spanish Jews, and merchants from Antwerp. Most were being persecuted by the Spanish who ruled most of Western Europe at the time; others were just the poor looking for work. Amsterdam was known for religious and ethnic tolerance, all were welcomed.

Another significant group that immigrated to Amsterdam in the 16th century were the Armenians. The Armenians brought in carpets, dyes, cotton, and spices from and around the world. They were wealthy traders and, with other rich merchants from Spain and Antwerp, could buy homes in the city center. The poor newcomers had to find a place in temporary and illegal shelters outside the city’s five-meter high wall.

This large migration created a housing shortage. (Influx of migrants and a housing shortage, sound familiar?) Before the 1600s, Amsterdam’s city walls and bastions encompassed the city with the Amstel River running through the center into the IJ and the Zuiderzee. The city was only one kilometer wide, with no room for urban expansion to accommodate the working class.

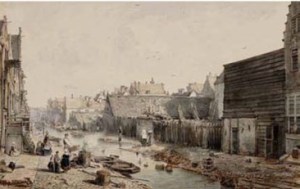

Before the multitudes, outside the city wall were meadows and farms interspersed with pottery and rope making workshops. It was quiet and peaceful until the throngs came. There was no room for the newcomers inside the wall, so they built their own shelters and houses, which were illegal. In 1609 there were about 3000 dwellings constructed between rectangular ditches.

In 1613 Amsterdam’s city fathers, wealthy oligarchs, embarked on a large-scale expansion project, which took 50 years to complete. First was the construction of the grachtengordel (canal belt) with the lofty names of Herengracht, Prinsengracht and the Keizersgracht where stately homes for wealthy merchants and administrators were built. They had direct access to waterways, along which they conducted their businesses.

The district just behind it, called Het Nieuwe Werck (The New Work), was where refugees, emigrants, and workers went to live because of the low rents. The streets and canals throughout the Jordaan were in line with the old ditches and paths dug in the Middle Ages by peat cultivators. That’s why the streets and canals are different compared to the rest of the city.

One of the low renters was a struggling painter, Rembrandt van Rijn, who lived in the Jordaan during his less successful period between 1656 and 1669. He could not afford to live in the city center. If he only knew what his paintings are worth today. He could live in Amsterdam’s Waldorf Astoria.

Rembrandt’s house was on the Rozengracht (Rose Canal is now a street). His studio was on the Bloemgracht (Flower Canal). The famous painter was buried in a poor man’s grave in the Westerkerk, next to the Jordaan, on the Prinsengracht (Prince Canal). Although he was a rich man, his destitute heirs could not afford a tombstone, so be careful where you walk when visiting the church. You could be standing on his torso.

There are many theories on how the neighborhood was called the Jordaan, I lean to the French version. Many of the district’s new residents during the 17th century were the Calvinistic Huguenots. It’s alleged they referred to the district as ‘le jardin’ (the garden), because streets were named after flowers and plants. Not knowing French, the Dutch pronounced it as the ‘Jordaan’. The lingo stuck.

In the Jordaan’s humble beginnings, all kinds of small lucrative businesses sprung up such as textile workshops, potteries, brewing and sugar refineries, tanneries and carpentries. Most residents were day laborers, journeymen and poor artists. The Dutch East India Company, founded in 1602, provided the residents with a lot of employment, from bakers and butchers to tailors and warehouse workers.

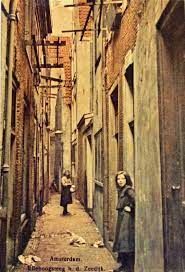

In the early days, the Jordaan was a pleasant place to live and work. Houses were built on stilts, open to sunlight and had courtyards. But as the population grew, there was a demand for more cheap housing. Although it was illegal, vulture slum landlords swooped in and built new houses in the courtyards in order to rent to more people. Many were built without the support of stilts and started to sink into the marshland.

Living conditions got worse over time. The Jordaan became a maze of tight corridors with shaky houses with rooms that were deprived of sunlight and fresh air. These small houses were crammed with large families living in one or, if you had extra money, two rooms. Many settled in cold attics or in damp basements. In 1873 there were 800 cellar houses in the Jordaan in which 3,372 persons lived, of which 954 were children under the age of ten. 76% of those basement dwellings were considered uninhabitable but were still inhabited. Part of the cellars were permanently waterlogged, and at the dawn of a new day, the first act was to pump it dry for usable floor space.

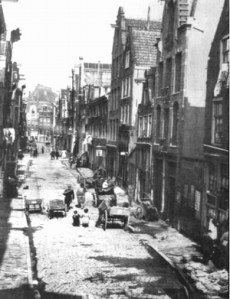

During the 18th and 19th centuries, due to wars and the French occupation, trade and shipping declined causing further poverty in the Jordaan. The community also suffered from cholera, nighttime itching from bed bugs, alcoholism, domestic abuse, unemployment and unsanitary conditions. Human waste was collected in buckets, so-called ‘beer buckets’. There was one on each floor or room. They were collected weekly by a cart or dumped with garbage into the canals. The stench caused a number of Jordaan’s canals to be filled in at the end of the century. Conditions were ripe for social unrest.

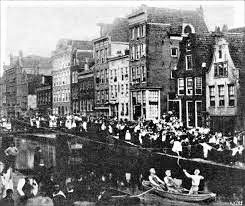

A popular game in the neighborhood was ‘eel pulling’, where a live eel is stretched on a rope above a canal and had to be pulled from a sailing boat. The police, at the instruction of the elite who claimed animal cruelty, banned the game. That did not sit well with the working class and one of their favorite sports.

On July 25, 1886, a rebellion, known as the Eel Riots, broke out on the Lindengracht (before it was filled in) when the police tried to stop the popular game by cutting the rope that held the eel. This caused an uproar and culminated in the demand for better living conditions. In the end, the army had to intervene killing 25 people, bringing the Eel Riots to an abrupt end.

After the Eel Riots, there was the Potato Riot in 1917 with nine dead and the Jordaanoproer (Jordan Riot) in 1934 that killed five. All this mayhem prompted the city council to thoroughly refurbish the Jordaan. In the 1920s, the socialist alderman Floor Wibaut built many affordable homes, giving the Jordaan some new life. The new housing associations also ensured better hygiene and indoor toilet facilities. Nevertheless, the Jordaan remained a neighborhood with a lot of poverty, unemployment and unattended grievances.

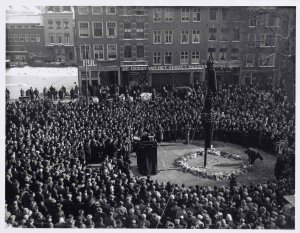

During the Second World War, the Jordaan’s communists organized the February Strike on February 25, 1941. They called on all Amsterdam workers to lay down their work for a day in protest against the German occupation and the persecution of Jews. The general strike lasted for two days; on February 26, 300,000 Amsterdammers joined the strike. Nine strikers died, dozens were injured, and 18 protesters were executed.

The Jordaan gradually degraded into a slum. After World War II, it was proposed to destroy the area completely and build new apartment buildings in its place. But on the initiative of a few impassioned residents, the Jordaan was saved from destruction and given a second life. A massive renovation was carried out in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1972 the neighborhood was declared a protected cityscape, which prevented excessive demolition.

Now, the Jordaan is known for being an art district and is one of the most desirable neighborhoods of Amsterdam to live in. Where 90,000 poor people used to live in cramped rooms, in 2022 around 18,000 well-off Amsterdammers live in one of the most upscale, expensive neighborhoods in the Netherlands.

Raised out of poverty, the Jordaan is now home to many modern art galleries, specialty shops and restaurants. Spend some quality time to walk around and visit the markets that are held regularly at Noordermarkt, the Westerstraat (the Lapjesmarkt textile market) and Lindengracht. You might want to soak in Jordaan’s history at Café t’Papeneiland, a traditional café-bar that opened on the corner of the Prinsengracht and Brouwersgracht in 1642.

Addendum: My paternal side of the family lived on several streets in the Jordaan from around 1800 to the early 1900s. In the 1920s, my grandparents bought a row house apartment building and moved to a newer more modern neighborhood on the other side of the city where my father, my brother and I were born.

© Jim Goyjer Photography and Article